One of the many gaps in my education was a definition of “Pantsing.” Any pop culture dictionary will tell you it means “pulling someone’s pants down” as a practical joke and that’s the only way I had heard it used until recently. There is, however, another common usage of the word in the writing world. It is a borrowed from an aviation term, “fly by the seat of your pants.” It means to write without a plan. No outline, no definitive plot, just an idea. Some people start without even a character study. They simply take the kernel of the idea, a “What if?” situation and run with it. They create that crappy first draft, then go back and re-write and re-write and, maybe, re-write again. Since the first thing they have to do is fix plot holes and inconsistencies, then character and timeline conflicts, then grammar and spelling, the revisions can take longer than the first draft.

One of the many gaps in my education was a definition of “Pantsing.” Any pop culture dictionary will tell you it means “pulling someone’s pants down” as a practical joke and that’s the only way I had heard it used until recently. There is, however, another common usage of the word in the writing world. It is a borrowed from an aviation term, “fly by the seat of your pants.” It means to write without a plan. No outline, no definitive plot, just an idea. Some people start without even a character study. They simply take the kernel of the idea, a “What if?” situation and run with it. They create that crappy first draft, then go back and re-write and re-write and, maybe, re-write again. Since the first thing they have to do is fix plot holes and inconsistencies, then character and timeline conflicts, then grammar and spelling, the revisions can take longer than the first draft.

In “Bird by Bird,” a book on the writing process by Anne Lamott, she tells of, literally, taking her manuscript apart. Spreading it out, scene by scene, on the livingroom floor “like a garden path made of tiles.” She rearranged the scenes, scribbled notes on them, did the third re-write, then took it to her editor, who rejected it again. After she told him the story, explained to him what she thought she was saying in the book, he said “….Go off somewhere and write me a treatment, a plot treatment. Tell me chapter by chapter what you just told me in the last half hour….” In other words, make an outline.

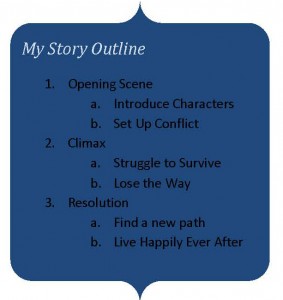

Because an outline doesn’t have to be bullet points or numbered sentences. An outline is a framework. It is sometimes a simple skeleton, but it may be a series of chapter summaries and character studies with actual muscle attached. There are authors who say they never plan ahead and have no problems with the pantsing method. Stephen King is one of them. If you have his raw talent, maybe you can do the same. But most people need a plan. A short summary that states what the idea is, how things get started and progress from point to point until they reach a satisfactory conclusion. It doesn’t have to be pretty, not even presentable, no one ever needs to see it except you.

I admit that there is such a thing as over-planning. Somewhere in all the books on writing that I have read over the years, I remember one author who said he sometimes works on his outline for a year or more before he starts to write. People who spend that much time preparing to write are probably in as much trouble as the ones who have to tear their books apart in rewrite. There is a middle ground. A place where you create an outline in a few hours or days, then move on to writing a crappy first draft that needs a couple of re-writes, but not total re-visioning.

I’ve been told by a few people that making an outline is too confining. They think following a plan stifles creativity. That might be true if the plan were a Law, but it’s not. Each day, as you sit down to write, review the day before, look at the outline to check your status, then pants it to the end of your writing time. The outline isn’t meant to be an auto-pilot, just a guidance system. If your characters suddenly take a left turn or a sudden dive, and the change seems to be an improvement, revise the outline. It’s easier than re-visioning the whole book. Find a middle ground. Somewhere between pantsing your way into free-fall and letting an outline control your muse. It is possible to fly without losing your way.

Comments are closed.